Focusing in on Refugee Children’s Lives

Children count for a disproportionate number of those affected by the crisis in Syria. To date, more than 40 per cent of all Syrian refugee children have fled to Lebanon; a quarter of whom are under the age of four. For many, their life experiences form a terrible mosaic of instability, poverty, loss and distress.

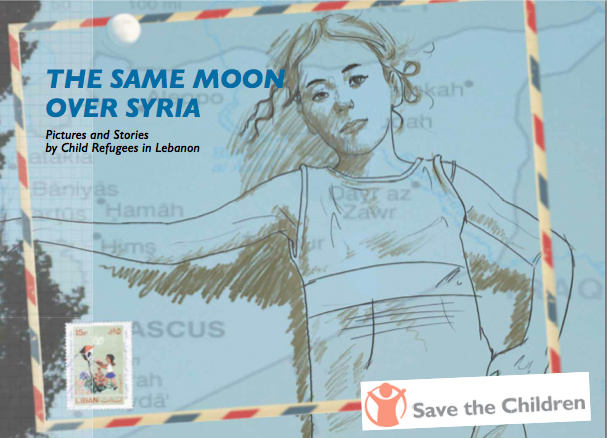

Save the Children Lebanon recently published a book of children’s testimonies and photographs, The Same Moon over Syria: Pictures and Stories by Child Refugees in Lebanon, highlighting some of the voices of Syrian refugee children. The book is part of Save the Children Lebanon’s ongoing mission to empower refugee children to become their own advocates, using such mediums as art, video, photography, poetry and animation to give expression their experiences. For the book project, four groups of 20 children children each attended a week long photography workshops, during which they were taught basic photography skills. They were then each given a camera and were free to document whatever they felt was important or interesting to them within their new environment and as well as the possessions that represented a link to their lives in Syria.

(click on the image to view the book)

(click on the image to view the book)

Over a two-month period, more than 7,000 photographs were taken by the children who participated in the workshops. The Same Moon Over Syria tells the stories behind the photographs of 30 of these children, who live in Informal Settlements, garages and other makeshift homes across the Bekaa Valley and Northern Lebanon. The images both document their immediate surroundings and offer a glimpse into their hopes, fears and dreams. Rania, 13, photographed a mobile phone, explaining it was given to her by a friend in Syria as a parting gift. “She is still in Syria but I don’t know anything about her anymore. The phone works but I can’t call my friend.”

Many of the testimonials reveal children who have been forced to grow up far too fast. “My father was detained at a checkpoint and tortured to death. They told us all his bones were broken”, says 11-year-old Salwa. Common to virtually every child’s story is a strong desire to return home, to build a better future for Syria, and a yearning for normalcy and security. Many speak of the monotony and boredom of life in the camps, bereft of toys, proper schooling or comforts of home. Yet every child expresses his or her experience of war and displacement differently. The book also reveals children who, despite the gravest of circumstances, embody an inspiring drive for liveliness, creativity and an appetite to learn. Their testimonies are both poignant and spirited, and in places, even light-hearted. Lamia, 12, photographed her younger sister who “always likes to pinch my things.” The book is a stark reminder of the human cost of conflict, and of the international community’s failure to ensure the children of Syria can grow up in the peaceful and protective environment they deserve.

Lebanon

Lebanon